General

Tata Electronics chip fab to open prototyping access for Indian startups

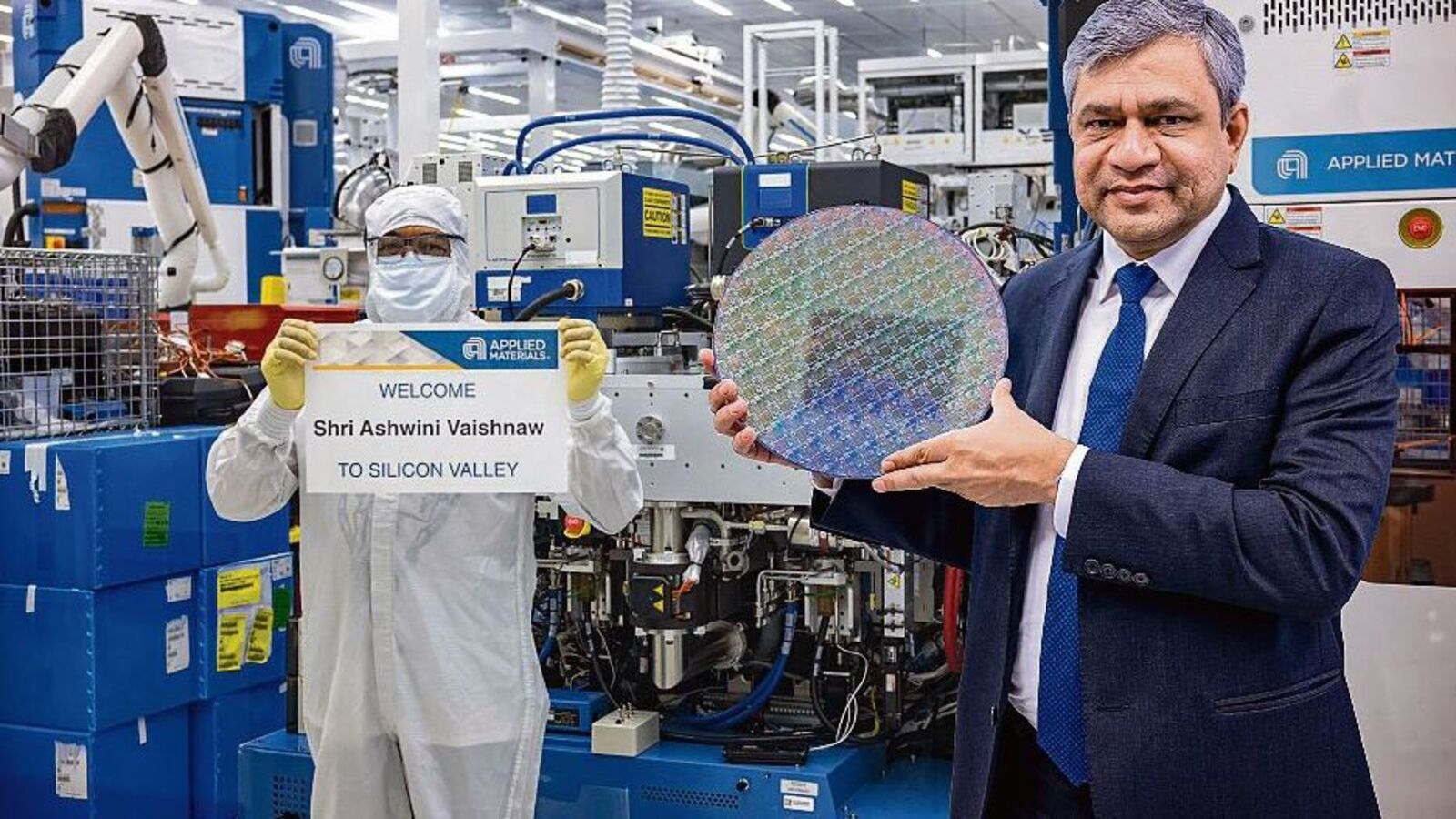

India’s upcoming semiconductor plant being developed by Tata Electronics will allow domestic startups to design and prototype chips locally. The move, confirmed by electronics and IT minister Ashwini Vaishnaw, aims to reduce reliance on overseas fabs and accelerate India’s chip innovation pipeline. India’s semiconductor ambitions are beginning to move beyond policy announcements and capital commitments […]

India’s upcoming semiconductor plant being developed by Tata Electronics will allow domestic startups to design and prototype chips locally. The move, confirmed by electronics and IT minister Ashwini Vaishnaw, aims to reduce reliance on overseas fabs and accelerate India’s chip innovation pipeline.

India’s semiconductor ambitions are beginning to move beyond policy announcements and capital commitments toward practical access for founders. The country’s first large-scale commercial chip fabrication facility, being developed by Tata Electronics, is expected to support Indian startups by allowing them to build and test prototype chips domestically—an inflection point for a hardware ecosystem that has long depended on foreign fabs.

The plan was outlined by Ashwini Vaishnaw, who said the facility would not be restricted to large corporate clients alone. Instead, it is being positioned as shared national infrastructure that can be accessed by early-stage chip design companies that currently struggle with high costs and long timelines abroad.

For Indian founders working on semiconductors, the announcement addresses a structural bottleneck that has slowed innovation for years: the absence of local fabrication and prototyping capacity.

From policy push to physical access

India has spent the past three years laying the policy groundwork for a domestic semiconductor industry, rolling out incentives under its chip manufacturing and design-linked incentive schemes. While these programs have helped attract global suppliers and catalyze design startups, actual chip fabrication has remained offshore—typically in Taiwan, South Korea, or the United States.

That dependence comes with steep trade-offs. Sending designs overseas for prototyping can cost startups millions of dollars, involve months-long wait times, and expose sensitive IP to geopolitical and supply-chain risks. For many young companies, it has effectively limited chip development to simulation rather than silicon.

Opening Tata Electronics’ fab to startup prototyping changes that equation. Local access means faster iteration cycles, lower logistical friction, and a clearer pathway from concept to commercialization.

Why Tata Electronics matters to the ecosystem

The choice of Tata Electronics as a cornerstone of this effort is significant. Part of the broader Tata Group, Tata Electronics has been steadily expanding from electronics manufacturing services into higher-value components and semiconductor packaging.

Its semiconductor plant—being developed with government backing—is expected to serve both domestic and international demand. Allowing startups to prototype chips there embeds innovation into the facility’s operating model rather than treating it purely as an industrial export asset.

For India’s chip design startups, this could replicate elements of ecosystems seen in Taiwan or South Korea, where proximity between design houses, fabs, and packaging units accelerates learning and talent development.

What startups stand to gain—and what remains unclear

Access to a domestic fab does not automatically guarantee affordability or scale. Much will depend on pricing structures, queue prioritization, and the extent to which the government subsidizes prototype runs for early-stage companies.

However, even limited access can be transformative. Prototype fabrication enables startups to validate performance, power efficiency, and manufacturability—critical steps before raising growth capital or signing enterprise customers.

It also signals credibility to global partners. A startup that can point to chips fabricated in India, under a national program, may find it easier to attract international customers wary of supply-chain concentration in East Asia.

Still, several operational questions remain open. The government has not yet detailed how startups will apply for access, whether there will be minimum order sizes, or how intellectual property protection will be handled within the facility.

A broader shift toward design-led manufacturing

India’s semiconductor push has often been framed as a race to build fabs. But policymakers increasingly acknowledge that long-term success depends on coupling manufacturing with indigenous design capability.

By linking Tata Electronics’ fabrication capacity with startup prototyping, the government is signaling that chip design—not just assembly or packaging—will be a strategic priority.

This matters in global context. As the US, Europe, and East Asia pour billions into semiconductor sovereignty, countries that combine design talent with manufacturing access are better positioned to capture value across the supply chain.

India already produces a large share of the world’s chip designers through its engineering workforce. The missing piece has been local silicon. Tata Electronics initiative attempts to close that gap.

Implications for investors and global partners

For investors, the move reduces execution risk in Indian semiconductor startups. Local prototyping shortens development timelines and lowers capital intensity, potentially making hardware ventures more attractive compared to their historical risk profiles.

Global semiconductor companies may also see opportunity. A growing base of Indian-designed chips, validated onshore, could feed into international supply chains, especially for automotive, industrial, and IoT applications.

At the same time, competition will intensify. As barriers to entry fall, more startups are likely to attempt chip development, raising the bar for differentiation and commercial viability.

Looking ahead

Tata Electronics’ semiconductor plant is not yet operational at full scale, and its success will hinge on execution as much as intent. But the decision to include startups from the outset reflects a more mature understanding of how semiconductor ecosystems are built.

If implemented effectively, the initiative could mark the moment when India’s chip story shifts from ambition to participation—giving domestic startups their first realistic chance to turn designs into working silicon without leaving the country.

For an ecosystem long constrained by distance and cost, that access could prove as important as the fab itself.